.thumb.jpg.ad9951633b024151d9ce002f6e96f160.jpg)

Oftentimes I can have a conversation with the average investor about markets/trading and know what they're going to say because the same questions and comments come up time after time. We're just wired to think short term and worry about the apocalypse du jour that's likely to make the market crash soon. Rarely do I hear "Jesse, what do you think is the right lifetime investment strategy to reach my long-term financial goals."

Something I've observed about option writing, is that at some point, since it's a strategy that requires you to act every month, you're going to deviate from the model because your emotions trick you into thinking you know better. The apocalypse du jour will take your mind captive, so just be aware of it. You're probably still going to eventually give in and do it even after reading this, because good advice is like Vitamin C that the body can't naturally retain on its own. It must constantly be injected!

You'll say "the market is at all time-highs, it can't possibly go higher!?" The next roll will come along, and you'll decide to sit it out for a month. In fact, almost every time it's time to roll, this thought will cross your mind. And if you act on this impulse history tells us there's a roughly 80% chance you'll miss a winning trade and the market will be even higher...or flat or not down much, all situations that lead to winning short put trades (one of the many attractive qualities of the strategy). So the next roll will come around, and now you're really stuck. You thought it was too high last month, and now it's even higher!

Stop and think about this for a second...go look up what the S&P 500 was at the day you were born. Since you're probably not going to do it, let me share some data.

Today: SPX $2,975

12/31/99: $1,469

12/31/89: $353

12/31/79: $108

12/31/69: $92

12/31/59: $60

Note this is just the S&P 500 cash index, which excludes dividends. Dividend adjusted, which all shareholders obviously get paid, the results are much more dramatic. By definition this means it was at "nose-bleed all time high levels" year after year after year, with the occasional multi year periods of temporary decline before it resumed the permanent uptrend. How else does something average 10% per year for a century other than routinely putting in new all-time highs?

So can you outguess the market? Anything is possible, but it's more probable that 10 years from now you'll look back and realize you'd have made a lot more money if you'd have just followed the dumb model. Just like most of us would if we look back at our investing career up to this point and realize we'd be better off today if we had kept it simple and bought and held a reasonable portfolio of equity ETF's or mutual funds or just sold a simple put each month. The markets are ready to endow us all with forever increasing wealth if we would just get out of our own way and allow it to happen.

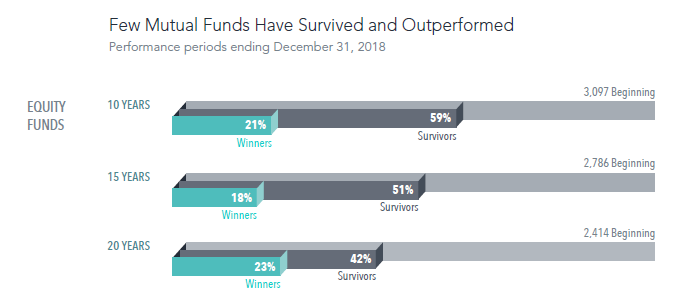

I believe a model is the ceiling on potential performance, not the floor. Any human intervention is likely going to cost us money over the long term. Our time is better spent in the strategy construction process than trying to outguess it during the heat of battle when emotions tend to give us tunnel vision. I believe in evidence based investing, so we can also look and try to learn lessons from the data. For example, Dimensional Fund Advisors regularly updates research about mutual funds. Here's what their most recently updated "2019 mutual fund landscape" study found.

So for example, 20 years ago, there were 2,414 stock mutual funds at the beginning of the period. By 12/31/2018, only 42% even still existed. Do funds shut down because their performance was great or because it was poor? And of those that survived, only 23% outperformed their prospectus benchmark. This includes the most talented market timers and stock pickers in the world, and only 23 out of 100 could add value, net of all costs, above a basic benchmark that is available today at almost no cost (and even no expense ratio in some situations). Note that this degree of outperformance is less than would be expected by random chance alone, so attempting to just find and invest with those few winners has not been a good approach either as the data shows there is a significant degree of randomness (aka luck) in performance data. And good luck is not something that is expected to persist in the future.

So what can we learn from this? If 77% of professionals can't time the market, do you really think you're going to be able to do it consistently enough over time to add value vs. just relaxing and following the simple model (meaning, the trade alerts)? When you get the urge to deviate off course, try laying down until that urge goes away. And if it's still there when you get up, ask yourself what you know that the rest of the market doesn't? A foundation of an efficient market is that all know relevant information is already reflected in the price, which is obvious in the above mutual fund data that highlights how hard it is to outguess it.

A better approach is to just be prepared for the inevitable periods of outstanding performance (like we've seen since launch), along with the inevitable periods of poor performance and even double digit declines in your account value. For example, don't put your emergency fund in the strategy. Don't take out a HELOC to invest more in the strategy. Just be patient and sensible. Surprise is the mother of panic, and if you're surprised in the future when we have a double digit portfolio drawdown (because we will), it means you haven't reviewed the charts in our strategy description post or read my posts like this that attempt to remind subscribers what to expect.

The market makes us money (geek speak, a combination of the equity, volatility, and term risk premiums), not my perfectly timed trade alerts. This also means the market will at times cause us to lose money, and my trade alerts will not prevent that from happening. We will accept what the markets give us, knowing that we get paid to bear risk that others don't want to take over the long term. For example, option buyers are typically hedging their position, and are willing to pay a premium to do that. We step in, and sensibly collect that premium, like an insurance company. So only take the risk that you have the ability (time horizon), willingness (emotional tolerance for volatility), and need (long term required rate of return to reach your goals) to take.

Above screenshot from Ben Carlson's excellent post that has related thinking: The Problem With Intuitive Investing

Jesse Blom is a licensed investment advisor and Vice President of Lorintine Capital, LP. He provides investment advice to clients all over the United States and around the world. Jesse has been in financial services since 2008 and is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ professional. Working with a CFP® professional represents the highest standard of financial planning advice. Jesse has a Bachelor of Science in Finance from Oral Roberts University. Jesse manages the Steady Momentum service, and regularly incorporates options into client portfolios.

Related articles

- Combining Momentum And Put Selling

- Combining Momentum And Put Selling (Updated)

- Steady Momentum ETF Portfolio

- Equity Index Put Writing For The Long Run

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.