Such lawsuits are common and typically lack merit because offering documents are properly drafted to protect the companies involved and disclose the risk.

I find it unlikely that the documents were not properly drafted. For instance, in one of the few actual UBS documents I could find on UBS’s yield enhancement strategies provided “yield enhancement strategy products are designed for investors with moderate risk tolerance who want to enhance the low to moderate return typically generated in a ‘flat’ or ‘sideways’ market.” That’s a great description for trading iron condors.

So, if the documents were fine (most likely, but you never know), what was the issue?Most likely overzealous brokers pushed the strategy without really understanding the risk profile.

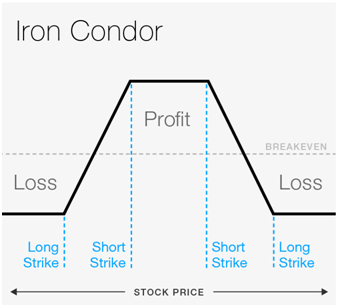

My takeaway from reading about this is two part. First, investors typically don’t understand options, and the media certainly does not. Most advisors do not either. For instance, the media has called the strategy used by UBS a “leveraged, esoteric options strategy.” Iron condors are neither esotericor typically leveraged. They are the definition of a defined risk option strategy. A profit/loss graph of an iron condor looks like:

There is a maximum loss on any single trade that can be controlled based on the strikes and premiums received. UBS’s strategy purportedly used iron condors on the S&P 500 index, the NASDAQ, and other “primary” market indexes – so volume should not have been an issue.

Other writers have demonstrated their ignorance of the strategy. One popular critique of the UBS strategy reads:

“The problems with YES began in 2018 with violent fluctuations in the S&P 500…The most volatile period was between October and December 2018, during which time the market declined 20%--then followed by a rebound of 12% through January 2019. The violent swings caused the premiums of both the put and call side of the iron condor strategy to spike, leading to losses on both sides of the trade.”

But this is practically impossible. An investor can’t experience losses on BOTH sides of the graph (in effect doubling the losses), unless the traders are idiots. The only way to have that happen is to close out one half of the trade for a loss, in the hopes that the profits on the other side will increase, but then the market whipsaws back, thus causing losses on both sides.

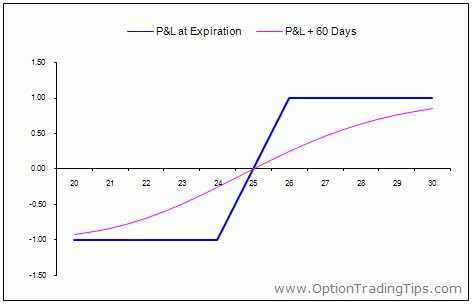

Of course, at this point, the strategy is no longer an iron condor. It’s a simple vertical spread:

The odd thing about this critique is that even vertical spreads have loss limits. Let’s say the UBS traders had a maximum loss rate of ten percent. A structured iron condor can have a max loss of ten percent the same as a vertical spread.

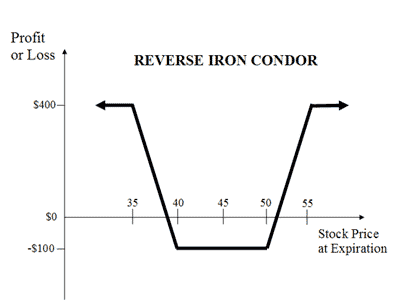

If the traders are trading to profit from time decay across multiple indexes, risk could be further controlled through the use of reverse iron condors that have a profit and loss graph of:

In the event of a large move, such a position could help offset losses. (There are other ways to protect against such a move as well – anything from simply buying long dated out of the money puts and calls to trading volatility instruments).

The problem with a normal iron condor in a low volatility market is that traders do not receive a very high premium for the risk they take. In order to get a 1% or 2% return per month, UBS traders would have to be taking risks that were outside of the “moderate” or “low” range. Traders probably started taking chances they shouldn’t have.

Much of the media has commented that the UBS traders “compounded” their results by trying to “make up” for losses after blowing up trades. (Who of us hasn’t done that?) Traders make trade adjustments or open new trades on the prediction that either (a) the price will return to the mean or (b) the price will continue moving. It appears the UBS traders made the bet that the price would continue moving, and instead it reverted to the mean.

Of course,when traders do that, they are no longer trading risk defined iron condors. They are making directional market bets – bets that if wrong, make the situation worse.

What can we, as option traders, learn from this?

- Trading is as much psychological, as it is methodical, even for supposed professionals. Losses will occur and decisions will be made trying to “make up” for losses rather than staying within stated trading guidelines. This is a mistake. Plan trades, plan for what happens when the trades go wrong, and when they do go wrong, stick to the plan. Sure you might occasionally “fix” what went wrong, but more often than not, you’ll likely make the situation worse;

- The general public views option as “high risk” investments. They are not, when handled properly. In fact, as option traders know, options can be used to mitigate risk. Try to combat the disinformation when you can;

- Don’t trust plaintiff class action lawyers.

I personally do not understand all of the class type legal advertising that exists because of the strategy. By all accounts, all UBS agreements require FINRA arbitration of individual claims. This greatly decreases the profit potential for attorneys, unless the client lost hundreds of thousands of dollars (in which case the client is probably not calling Saul from the internet for the case). Strangely, that is what can currently be seen.

Christopher Welsh is a licensed investment advisor and president of LorintineCapital, LP. He provides investment advice to clients all over the United States and around the world. Christopher has been in financial services since 2008 and is a CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™. Working with a CFP® professional represents the highest standard of financial planning advice. Christopher has a J.D. from the SMU Dedman School of Law, a Bachelor of Science in Computer Science, and a Bachelor of Science in Economics. Christopher is a regular contributor to the Steady Options Anchor Trades and Lorintine CapitalBlog.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.