.thumb.jpg.73d7f4c2b18b21fef691300c83ad64ae.jpg)

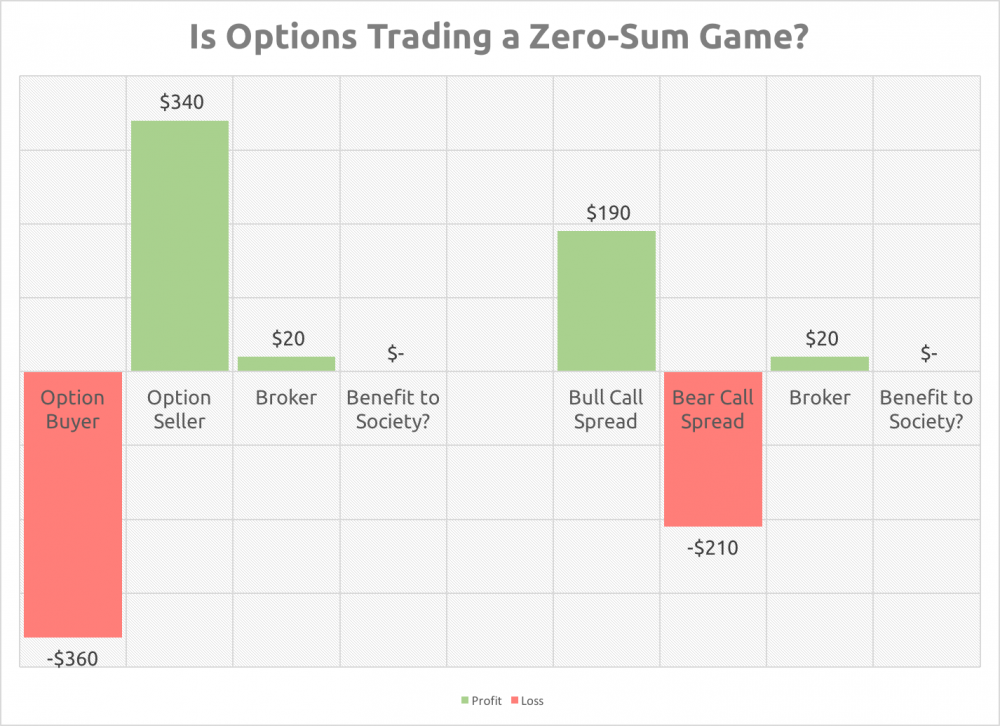

See, I’m an options nerd – I love the power, math, and flexibility of the instrument. Therefore, I get quite animated when I hear criticisms against options trading. Besides the risk, leverage, and incorrect blame for options causing the housing crisis, one of such statements is that options trading provides “no value – it’s a zero-sum game.”

This bothers me and I hope it bothers you, my fellow options-trading enthusiast. Is options trading really a zero-sum game? Am I no better than a gambler or a pickpocket taking a fellow trader’s hard-earned money?

Conventional wisdom might say it is zero-sum, but for this article, let’s discuss a non-conventional view premised on the question of: what value and utility options bring markets and society?

What does it mean to be a “Zero-Sum Game?”

A zero-sum game is one where there needs to be a loser for every winner. This interplay between winning and losing creates a net value of zero, a world where your chance to win is all or none.

Las Vegas and sports betting books put this in terms of a pick ‘em bet, where you choose your team to win the game, regardless of points or spreads between the two competitors. If you bet on Team A and they win the game, you win.

However, if you win, the counterparty (who chose Team B) loses. There’s no splitting earnings, no recompense for effort, no crying in baseball. You win or you don’t win.

We’ll let this stand as our general understanding of zero-sum game and see if the rules explained above have any meaning or relevancy to options trading.

Is Stock Trading a “Zero-Sum Game?”

If we apply our general understanding of what the meaning of a zero-sum game is, then would traditional stock trading (buying and selling) fit the description?

With stock trading, as in any type of trading, there is a buyer and seller and with each dollar the stock moves one profits while the other takes real losses (shorts) or opportunity losses (sellers).

However, conventional wisdom would say no, stock trading is not zero-sum. When buying or selling stocks, you create value. You create value for yourself in terms of a potential for unlimited gains, additional income in the form of dividend, and capital growth over time.

You also create value for the company by providing needed capital that is used for expansion and growth opportunities, the creation of dividends for other investors, and a way for the company to continue to produce, modernize, and be/become profitable. This type of value also creates a larger benefit for the community in the form of products and services, jobs, a taxable entity, corporate partner for social and charitable causes, etc.

Stock trading is far from a zero-sum game. It is, in many respects, a value proposition that provides individual (micro) and societal (macro) benefits.

Surely Trading Options is Zero-Sum?

So, zero-sum is winning and losing in absolute states, if you continued to buy into the argument laid out so far. Accepting the value creation proposition of stock trading and the ripple effect it has, isn’t it logical to afford options the same opportunity to demonstrate value? Why must others peg them a zero-sum game of winners matched with losers?

Let’s make an analogy of options trading with that of owning auto insurance. Insurance as we know provides assurance and piece of mind against the potential for loss based on pure risks. Pure risks are those that are unforeseen, accidental in nature, and not based on winning or losing.

You buy auto insurance to protect against the financial loss associated with owning and operating an automobile, including financial loss for physical damage caused by you or to you by others, as well as bodily injury that may occur as the result of an accident that caused an injury to you or another person.

You pay a premium, which is the exchange of value between you and the insurance company commensurate to the risk of the provided insurance. Under this scenario there are no winners or losers. In fact, the expectation is that the insurance company remains solvent and profitable in order to protect you against financial loss. Even if you never experience an accident or other insurable loss to your vehicle, the premium you paid is the price for the peace of mind you receive.

That feels like you received something of value (protection) in exchange for something of value (premiums paid).

Options operate in the exact same manner. You pay (or receive a premium) in exchange for the ability to either lock in a price for stock you own or are looking to purchase, or to protect the value of the stock (or your portfolio) in the event the market moves contrary to how you believe. If the option expires worthless, you don’t lose if you paid premium, in the case of an options holder, and certainly do not lose if you receive a premium, in the case of an options writer.

The Origins of Options as a Risk Transfer Tool

We will further develop this notion of options as an insurance tool by looking at the history of options. The origin of both options and futures begins with speculators taking bets on various harvests more than two thousand years ago in both Greece and Japan. Options came to America in 1872 via OTC puts and calls introduced by Russell Sage. However, the matching of buyers and sellers was a laborious manual process and struggled with manipulation.

Russell Sage Portrait

Then sprung up “bucket shops,” where traders would bet on the movement of stock prices without owning the shares. This, basically illegal activity, of course, does not bode well for the argument that options are more than zero-sum, but bear with me.

The activity of these bucket shops attracted regulatory authorities and, finally, some control over OTC options markets came down from the SEC. However, trading didn’t grow until the 70’s when the Chicago Board of Trade saw a significant decline in commodity futures and decided to create an official, regulated exchange (CBOE) for options in 1973. The exchange opened with call contracts only. The put contract came 4 years later.

The new exchange, run by those with extensive futures experience, meant options could be used not only as a speculation tool but as a risk transfer tool. With a strong exchange and renewed market confidence in a fungible financial product, finance saw the rise of options as not only a trading vehicle but also as a risk transfer tool.

What I mean by “Risk transfer” is that of taking potential for loss and transferring it to another party for the exchange of value – in legal terms this would be a consideration.

Yes, the same consideration which is necessary for insurance policies to be legally binding contracts. Alas, we’ve finally come back to the insurance company example where a consideration (premium) for the insurance company to insure the risk for potential financial loss (a reduction in value), not based on the actual experience of the loss but the potential for the loss.

Options operate in a similar manner. You pay or receive a premium based on a desire to protect value, peg profitability at a certain level, or increase income based on the current or future market sentiment. An insurer takes the opposite side, in this case being the options seller via the matching powers of the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC). The OCC creates binding contracts and provide a liquid, orderly, and efficient marketplace by which the exchanges operate.

If exercised, you meet the terms of the contract and the transaction ends. If the option expires worthless, you benefited from the protection provided. If the contract moves in a direction counter to your intuition, you can enter in to a closing transaction prior to expiration for a resulting limited gain or loss.

Everything described about the nature of options in the case of their use as a risk transfer tool makes them far from a zero-sum game, with its absolutes on winning and losing.

Options are very much a value proposition that provides intrinsic and real value, regardless of the way they’re utilized.

Hedgers vs. Speculators: The Counterparty Interaction Between Profit-Protection and Profit-Seeking

The OCC creates an offset for options trades, matching buyers and sellers to create a counterparty relationship and increase the efficiency of the marketplace. Hedgers tend to be buyers, seeking to protect a position against adverse bullish or bearish moves, and generally hold for the duration of the contract. Speculators seek profit and can remove themselves from an unfavorable position with a closing transaction. This means that the counterparty interaction between those seeking to protect profit (buyers or hedgers in most instances) and profit-seekers (sellers or speculators) provide tremendous value to the marketplace.

The counterparty in many options trades are hedgers who are “paying for insurance” as opposed to directly competing in opposing positions. Speculators tend to move in and out of positions more rapidly as well as close their positions before expiration.

This all stands to reason; a trader has a higher risk for loss taking a speculative stance should the position move even $0.01 in-the-money before expiration. Closing a position protects the trader and further preserves the balance between profit and protection, with a nice byproduct of liquidity along the way.

The Price Discovery & Stability Argument

Finally, let’s briefly discuss what is the price discovery and stability argument as it relates to market supply and demand in determining the price of an option.

The price discovery argument is one that is applied to trading futures contracts and used to determine spot prices for such commodities as corn, wheat, oil, and cattle. The close relationship futures and options have make the argument just as much relevant to options, and more specifically their pricing and hedging capability.

Options pricing, being based on implied volatility (IV),creates a voting machine of sorts between buyers and sellers. The IV can be translated to expected price moves in the underlying stock, which helps prepare both traders and the underlying before an event. These signals allow traders to buy protection and put on hedges, which takes us back to the “insurance value” argument.

Closing Thoughts

Despite a bumpy history, options demonstrate a significant value proposition to modern markets and modern traders. It’s unfair to say that options trading is a zero-sum game only suitable for gamblers and market makers and unsuitable for the at-home, retail options trader.

So take pride the next time you sell that valuable put because you may have just provided someone extremely valuable security and peace of mind – and if you make a little money in the process, then even better.

Drew Hilleshiem is the Co-Founder and CEO of OptionAutomator, an options trading technology startup offering a free options screener that leverages Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) algorithms to force-rank relevancy of daily options opportunities against user’s individual trading criteria. He is passionate to help close the gap between Wall Street and Main Street with both technology and blogging. You can follow Drew via @OptionAutomator on Twitter.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.